Astronomy Night At The White House

Astronomy Night at the White House

NASA took over the White House Instagram today in honor of Astronomy Night to share some incredible views of the universe and the world around us. Check out more updates from the astronauts, scientists, and students on South Lawn.

Here’s a nighttime view of Washington, D.C. from the astronauts on the International Space Station on October 17. Can you spot the White House?

Check out this look at our sun taken by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory. The SDO watches the sun constantly, and it captured this image of the sun emitting a mid-level solar flare on June 25. Solar flares are powerful bursts of radiation. Harmful radiation from a flare can’t pass through Earth’s atmosphere to physically affect humans on the ground. But when they’re intense enough, they can disturb the atmosphere in the layer where GPS and communications signals travel.

Next up is this incredible view of Saturn’s rings, seen in ultraviolet by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. Hinting at the origin of the rings and their evolution, this ultraviolet view indicates that there’s more ice toward the outer part of the rings than in the inner part.

Take a look at the millions of galaxies that populate the patch of sky known as the COSMOS field, short for Cosmic Evolution Survey. A portion of the COSMOS field is seen here by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope. Even the smallest dots in this image are galaxies, some up to 12 billion light-years away. The picture is a combination of infrared data from Spitzer (red) and visible-light data (blue and green) from Japan’s Subaru telescope atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii. The brightest objects in the field are more than ten thousand times fainter than what you can see with the naked eye.

This incredible look at the Cat’s Eye nebula was taken from a composite of data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and Hubble Space Telescope. This famous object is a so-called planetary nebula that represents a phase of stellar evolution that the Sun should experience several billion years from now. When a star like the Sun begins to run out of fuel, it becomes what is known as a red giant. In this phase, a star sheds some of its outer layers, eventually leaving behind a hot core that collapses to form a dense white dwarf star. A fast wind emanating from the hot core rams into the ejected atmosphere, pushes it outward, and creates the graceful filamentary structures seen with optical telescopes.

This view of the International Space Station is a composite of nine frames that captured the ISS transiting the moon at roughly five miles per second on August 2. The International Space Station is a unique place—a convergence of science, technology, and human innovation that demonstrates new technologies and makes research breakthroughs not possible on Earth. As the third brightest object in the sky, the International Space Station is easy to see if you know when to look up. You can sign up for alerts and get information on when the International Space Station flies over you at spotthestation.nasa.gov. Thanks for following along today as NASA shared the view from astronomy night at the White House. Remember to look up and stay curious!

More Posts from Nasa and Others

Sending Science to Space (and back) 🔬🚀

This season on our NASA Explorers video series, we’ve been following Elaine Horn-Ranney Ph.D and Parastoo Khoshaklagh Ph.D. as they send their research to the space station.

From preparing the experiment in the lab….

To training the astronauts to perform the science…

To watching it launch to space…

To conducting the science aboard the space station, we’ve been there every step of the way.

Now you can follow along with the whole journey!

Binge watch all of NASA Explorers season 4: Microgravity HERE

Want to keep up with space station research? Follow ISS Research on Twitter.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

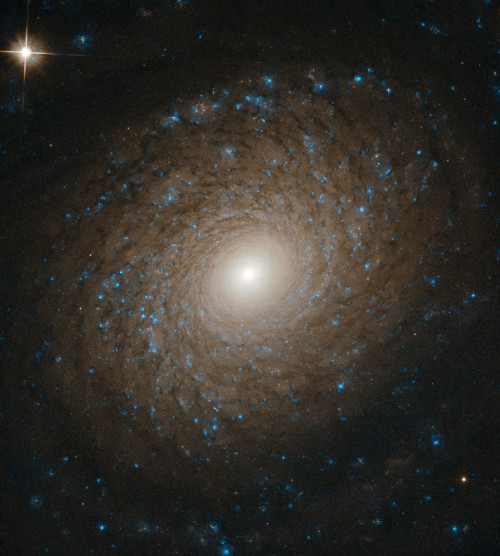

Flawless. Gorgeous. Stellar.

You probably think this post is about you. Well, it could be.

In this image taken by our Hubble Space Telescope, we see a spiral galaxy with arms that widen as they whirl outward from its bright core, slowly fading into the emptiness of space. Click here to learn more about this beautiful galaxy that resides 70 million light-years away.

Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, L. Ho Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

The twin Voyager spacecraft, which launched in 1977, are our ambassadors to the rest of the Milky Way, destined to continue orbiting the center of our galaxy for billions of years after they stop communicating with Earth. On Aug. 25, 2012, Voyager 1 became the first human-made object to enter interstellar space, and Voyager 2 is expected to cross over in the next few years. At age 40, the Voyagers are the farthest and longest-operating spacecraft and still have plenty more to discover. This poster captures the spirit of exploration, the vastness of space and the wonder that has fueled this ambitious journey to the outer planets and beyond.

Enjoy this and other Voyager anniversary posters. Download them for free here: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/downloads/

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Solar System: Things to Know This Week

With only four months left in the mission, Cassini is busy at Saturn. The upcoming cargo launch, anniversaries and more!

As our Cassini spacecraft made its first-ever dive through the gap between Saturn and its rings on April 26, 2017, one of its imaging cameras took a series of rapid-fire images that were used to make this movie sequence. Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute/Hampton University

1-3. The Grand Finale

Our Cassini spacecraft has begun its final mission at Saturn. Some dates to note:

May 28, 2017: Cassini makes its riskiest ring crossing as it ventures deeper into Saturn's innermost ring (D ring).

June 29, 2017: On this day in 2004, the Cassini orbiter and its travel companion the European Space Agency's Huygens probe arrived at Saturn.

September 15, 2017: In a final, spectacular dive, Cassini will plunge into Saturn - beaming science data about Saturn's atmosphere back to Earth to the last second. It's all over at 5:08 a.m. PDT.

More about the Grand Finale

4. Cargo Launch to the International Space Station

June 1, 2017: Target date of the cargo launch. The uncrewed Dragon spacecraft will launch on a Falcon 9 from Launch Complex 39A at our Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The payload includes NICER, an instrument to measure neutron stars, and ROSA, a Roll-Out Solar Array that will test a new solar panel that rolls open in space like a party favor.

More

5. Sojourner

July 4, 2017: Twenty years ago, a wagon-sized rover named Sojourner blazed the trail for future Mars explorers - both robots and, one day, humans. Take a trip back in time to the vintage Mars Pathfinder websites:

More

6. Voyager

August 20, 2017: Forty years and still going strong, our twin Voyagers mark 40 years since they left Earth.

More

7. Total Solar Eclipse

August 21, 2017: All of North America will be treated to a rare celestial event: a total solar eclipse. The path of totality runs from Oregon to South Carolina.

More

8. From Science Fiction to Science Fact

Light a candle for the man who took rocketry from science fiction to science fact. On this day in 1882, Robert H. Goddard was born in Worcester, Massachusetts.

More

9. Looking at the Moon

October 28, 2017: Howl (or look) at the moon with the rest of the world. It's time for the annual International Observe the Moon Night.

More

10. Last Human on the Moon

December 13, 2017: Forty-five years ago, Apollo 17 astronaut Gene Cernan left the last human footprint on the moon.

More

Discover more lists of 10 things to know about our solar system HERE.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

5 Out-of-this-world Facts About Our Iconic Vehicle Assembly Building!

The Vehicle Assembly Building, or VAB, at our Kennedy Space Center in Florida, is the only facility where assembly of a rocket occurred that carried humans beyond low-Earth orbit and on to the Moon. For 30 years, its facilities and assets were used during the Space Shuttle Program and are now available to commercial partners as part of our agency’s plan in support of a multi-user spaceport. To celebrate the VAB’s continued contribution to humanity’s space exploration endeavors, we’ve put together five out-of-this-world facts for you!

1. It’s one of the largest buildings in the world by area, the VAB covers eight acres, is 525 feet tall and 518 feet wide.

Aerial view of the Vehicle Assembly Building with a mobile launch tower atop a crawler transporter approaching the building.

2. The VAB was constructed for the assembly of the Apollo/Saturn V Moon rocket, the largest rocket made by humans at the time.

An Apollo/Saturn V facilities Test Vehicle and Launch Umbilical Tower (LUT) atop a crawler-transporter move from the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) on the way to Pad A on May 25, 1966.

3. The building is home to the largest American flag, a 209-foot-tall, 110-foot-wide star spangled banner painted on the side of the VAB.

Workers painting the Flag on the Vehicle Assembly Building on January 2, 2007.

4. The tallest portions of the VAB are its 4 high bays. Each has a 456-foot-high door. The doors are the largest in the world and take about 45 minutes to open or close completely.

A mobile launcher, atop crawler-transporter 2, begins the move into High Bay 3 at the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) on Sept. 8, 2018.

5. After spending more than 50 years supporting our human spaceflight programs, the VAB received its first commercial tenant – Northrop Grumman Corporation – on August 16, 2019!

A model of Northrop Grumman’s OmegA launch vehicle is flanked by the U.S. flag and a flag bearing the OmegA logo during a ribbon-cutting ceremony Aug. 16 in High Bay 2 of the Vehicle Assembly Building.

Whether the rockets and spacecraft are going into Earth orbit or being sent into deep space, the VAB will have the infrastructure to prepare them for their missions.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Pi Guides the Way

It may be irrational but pi plays an important role in the everyday work of scientists at NASA.

What Is Pi ?

Pi is the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter. It is also an irrational number, meaning its decimal representation never ends and it never repeats. Pi has been calculated to more than one trillion digits,

Why March 14?

March 14 marks the yearly celebration of the mathematical constant pi. More than just a number for mathematicians, pi has all sorts of applications in the real world, including on our missions. And as a holiday that encourages more than a little creativity – whether it’s making pi-themed pies or reciting from memory as many of the never-ending decimals of pi as possible (the record is 70,030 digits).

While 3.14 is often a precise enough approximation, hence the celebration occurring on March 14, or 3/14 (when written in standard U.S. month/day format), the first known celebration occurred in 1988, and in 2009, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution designating March 14 as Pi Day and encouraging teachers and students to celebrate the day with activities that teach students about pi.

5 Ways We Use Pi at NASA

Below are some ways scientists and engineers used pi.

Keeping Spacecraft Chugging Along

Propulsion engineers use pi to determine the volume and surface area of propellant tanks. It’s how they size tanks and determine liquid propellant volume to keep spacecraft going and making new discoveries.

Getting New Perspectives on Saturn

A technique called pi transfer uses the gravity of Titan’s moon, Titan, to alter the orbit of the Cassini spacecraft so it can obtain different perspectives of the ringed planet.

Learning the Composition of Asteroids

Using pi and the asteroid’s mass, scientists can calculate the density of an asteroid and learn what it’s made of--ice, iron, rock, etc.

Measuring Craters

knowing the circumference, diameter and surface area of a crater can tell scientists a lot about the asteroid or meteor that may have carved it out.

Determining the Size of Exoplanets

Exoplanets are planets that orbit suns other than our own and scientists use pi to search for them. The first step is determining how much the light curve of a planet’s sun dims when a suspected planets passes in front of it.

Want to learn more about Pi? Visit us on Pinterest at: https://www.pinterest.com/nasa/pi-day/

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

25 Years in Space for ESA & NASA’s Sun-Watching SOHO

A quarter-century ago, the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) launched to space. Its 25 years of data have changed the way we think about the Sun — illuminating everything from the Sun’s inner workings to the constant changes in its outermost atmosphere.

SOHO — a joint mission of the European Space Agency and NASA — carries 12 instruments to study different aspects of the Sun. One of the gamechangers was SOHO’s coronagraph, a type of instrument that uses a solid disk to block out the bright face of the Sun and reveal the relatively faint outer atmosphere, the corona. With SOHO’s coronagraph, scientists could image giant eruptions of solar material and magnetic fields, called coronal mass ejections, or CMEs. SOHO’s images revealed shape and structure of CMEs in breathtaking detail.

These solar storms can impact robotic spacecraft in their path, or — when intense and aimed at Earth — threaten astronauts on spacewalks and even disrupt power grids on the ground. SOHO is particularly useful in viewing Earth-bound storms, called halo CMEs — so called because when a CME barrels toward us on Earth, it appears circular, surrounding the Sun, much like watching a balloon inflate by looking down on it.

Before SOHO, the scientific community debated whether or not it was even possible to witness a CME coming straight toward us. Today, SOHO images are the backbone of space weather prediction models, regularly used in forecasting the impacts of space weather events traveling toward Earth.

Beyond the day-to-day monitoring of space weather, SOHO has been able to provide insight about our dynamic Sun on longer timescales as well. With 25 years under its belt, SOHO has observed a full magnetic cycle — when the Sun’s magnetic poles switch places and then flip back again, a process that takes about 22 years in total. This trove of data has led to revolutions in solar science: from revelations about the behavior of the solar core to new insight into space weather events that explode from the Sun and travel throughout the solar system.

Data from SOHO, sonified by the Stanford Experimental Physics Lab, captures the Sun’s natural vibrations and provides scientists with a concrete representation of its dynamic movements.

The legacy of SOHO’s instruments — such as the extreme ultraviolet imager, the first of its kind to fly in orbit — also paved the way for the next generation of NASA solar satellites, like the Solar Dynamics Observatory and STEREO. Even with these newer instruments now in orbit, SOHO’s data remains an invaluable part of solar science, producing nearly 200 scientific papers every year.

Relatively early in its mission, SOHO had a brush with catastrophe. During a routine calibration procedure in June 1998, the operations team lost contact with the spacecraft. With the help of a radio telescope in Arecibo, the team eventually located SOHO and brought it back online by November of that year. But luck only held out so long: Complications from the near loss emerged just weeks later, when all three gyroscopes — which help the spacecraft point in the right direction — failed. The spacecraft was no longer stabilized. Undaunted, the team’s software engineers developed a new program that would stabilize the spacecraft without the gyroscopes. SOHO resumed normal operations in February 1999, becoming the first spacecraft of its kind to function without gyroscopes.

SOHO’s coronagraph have also helped the Sun-studying mission become the greatest comet finder of all time. The mission’s data has revealed more than 4,000 comets to date, many of which were found by citizen scientists. SOHO’s online data during the early days of the mission made it possible for anyone to carefully scrutinize a image and potentially spot a comet heading toward the Sun. Amateur astronomers from across the globe joined the hunt and began sending their findings to the SOHO team. To ease the burden on their inboxes, the team created the SOHO Sungrazer Project, where citizen scientists could share their findings.

Keep up with the latest SOHO findings at nasa.gov/soho, and follow along with @NASASun on Twitter and facebook.com/NASASunScience.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Voyager: The Space Between

Our Voyager 1 spacecraft officially became the first human-made object to venture into interstellar space in 2012.

Whether and when our Voyager 1 spacecraft broke through to interstellar space, the space between stars, has been a thorny issue.

In 2012, claims surfaced every few months that Voyager 1 had “left our solar system.” Why had the Voyager team held off from saying the craft reached interstellar space until 2013?

Basically, the team needed more data on plasma, which is an ionozied gas that exists throughout space. (The glob of neon in a storefront sign is an example of plasma).

Plasma is the most important marker that distinguishes whether Voyager 1 is inside the solar bubble, known as the heliosphere. The heliosphere is defined by the constant stream of plasma that flows outward from our Sun – until it meets the boundary of interstellar space, which contains plasma from other sources.

Adding to the challenge: they didn’t know how they’d be able to detect it.

No one has been to interstellar space before, so it’s like traveling with guidebooks that are incomplete.

Additionally, Voyager 1’s plasma instrument, which measures the density, temperature and speed of plasma, stopped working in 1980, right after its last planetary flyby.

When Voyager 1 detected the pressure of interstellar space on our heliosphere in 2004, the science team didn’t have the instrument that would provide the most direct measurements of plasma.

Voyager 1 Trajectory

Instead, they focused on the direction of the magnetic field as a proxy for source of the plasma. Since solar plasma carries the magnetic field lines emanating from the Sun and interstellar plasma carries interstellar magnetic field lines, the directions of the solar and interstellar magnetic fields were expected to differ.

Voyager 2 Trajectory

In May 2012, the number of galactic cosmic rays made its first significant jump, while some of the inside particles made their first significant dip. The pace of change quickened dramatically on July 28, 2012. After five days, the intensities returned to what they had been. This was the first taste test of a new region, and at the time Voyager scientists thought the spacecraft might have briefly touched the edge of interstellar space.

By Aug. 25, when, as we now know, Voyager 1 entered this new region for good, all the lower-energy particles from inside zipped away. Some inside particles dropped by more than a factor of 1,000 compared to 2004. However, subsequent analysis of the magnetic field data revealed that even though the magnetic field strength jumped by 60% at the boundary, the direction changed less than 2 degrees. This suggested that Voyager 1 had not left the solar magnetic field and had only entered a new region, still inside our solar bubble, that had been depleted of inside particles.

Then, in April 2013, scientists got another piece of the puzzle by chance. For the first eight years of exploring the heliosheath, which is the outer layer of the heliosphere, Voyager’s plasma wave instrument had heard nothing. But the plasma wave science team had observed bursts of radio waves in 1983 and 1984 and again in 1992 and 1993. They determined these bursts were produced by the interstellar plasma when a large outburst of solar material would plow into it and cause it to oscillate.

It took about 400 days for such solar outbursts to reach interstellar space, leading to an estimated distance of 117 to 177 AU (117 to 177 times the distance from the Sun to the Earth) to the heliopause.

Then on April 9, 2013, it happened: Voyager 1’s plasma wave instrument picked up local plasma oscillations. Scientists think they probably stemmed from a burst of solar activity from a year before. The oscillations increased in pitch through May 22 and indicated that Voyager was moving into an increasingly dense region of plasma.

The above soundtrack reproduces the amplitude and frequency of the plasma waves as “heard” by Voyager 1. The waves detected by the instrument antennas can be simply amplified and played through a speaker. These frequencies are within the range heard by human ears.

When they extrapolated back, they deduced that Voyager had first encountered this dense interstellar plasma in Aug. 2012, consistent with the sharp boundaries in the charged particle and magnetic field data on Aug. 25.

In the end, there was general agreement that Voyager 1 was indeed outside in interstellar space, but that location comes with some disclaimers. They determined the spacecraft is in a mixed transitional region of interstellar space. We don’t know when it will reach interstellar space free from the influence of our solar bubble.

Voyager 1, which is working with a finite power supply, has enough electrical power to keep operating the fields and particles science instruments through at least 2020, which will make 43 years of continual operation.

Voyager 1 will continue sending engineering data for a few more years after the last science instrument is turned off, but after that it will be sailing on as a silent ambassador.

In about 40,000 years, it will be closer to the star AC +79 3888 than our own Sun.

And for the rest of time, Voyager 1 will continue orbiting around the heart of the Milky Way galaxy, with our Sun but a tiny point of light among many.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Celebrating Women’s Equality Day Across NASA

August 26 is celebrated in the United States as Women’s Equality Day. On this day in 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment was signed into law and American women were granted the constitutional right to vote. The suffragists who fought hard for a woman’s right to vote opened up doors for trailblazers who have helped shape our story of spaceflight, research and discovery. On Women’s Equality Day, we celebrate women at NASA who have broken barriers, challenged stereotypes and paved the way for future generations. This list is by no means exhaustive.

Rocket Girls and the Advent of the Space Age

In the earliest days of space exploration, most calculations for early space missions were done by “human computers,” and most of these computers were women. These women's calculations helped the U.S. launch its first satellite, Explorer 1. This image from 1953, five years before the launch of Explorer 1, shows some of those women on the campus of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

These women were trailblazers at a time when most technical fields were dominated by white men. Janez Lawson (seen in this photo), was the first African American hired into a technical position at JPL. Having graduated from UCLA with a bachelor's degree in chemical engineering, she later went on to have a successful career as a chemical engineer.

Katherine Johnson: A Champion for Women’s Equality

Mathematician Katherine Johnson, whose life story was told in the book and film "Hidden Figures," is 101 years old today! Coincidentally, Johnson’s birthday falls on August 26: which is appropriate, considering all the ways that she has stood for women’s equality at NASA and the country as a whole.

Johnson began her career in 1953 at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), the agency that preceded NASA, one of a number of African-American women hired to work as "human computers.” Johnson became known for her training in geometry, her leadership and her inquisitive nature; she was the only woman at the time to be pulled from the computing pool to work with engineers on other programs.

Johnson was responsible for calculating the trajectory of the 1961 flight of Alan Shepard, the first American in space, as well as verifying the calculations made by electronic computers of John Glenn’s 1962 launch to orbit and the 1969 Apollo 11 trajectory to the moon. She was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor, by President Barack Obama on Nov. 24, 2015.

JoAnn Morgan: Rocket Fuel in Her Blood

JoAnn Morgan was an engineer at Kennedy Space Center at a time when the launch room was crowded with men. In spite of working for all of the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs, and being promoted to a senior engineer, Morgan was still not permitted in the firing room at liftoff — until Apollo 11, when her supervisor advocated for her because of her superior communication skills. Because of this, Morgan was the instrumentation controller — and the only woman — in the launch room for the Apollo 11 liftoff.

Morgan’s career at NASA spanned over 45 years, and she continued to break ceiling after ceiling for women involved with the space program. She excelled in many other roles, including deputy of Expendable Launch Vehicles, director of Payload Projects Management and director of Safety and Mission Assurance. She was one of the last two people who verified the space shuttle was ready to launch and the first woman at KSC to serve in an executive position, associate director of the center.

Oceola (Ocie) Hall: An Advocate for NASA Women

Oceola Hall worked in NASA’s Office of Diversity and Equal Opportunity for over 25 years. She was NASA’s first agency-wide Federal Women’s program manager, from 1974 – 1978. Hall advanced opportunities for NASA women in science, engineering and administrative occupations. She was instrumental in initiating education programs for women, including the Simmons College Strategic Leadership for Women Program.

Hall’s outstanding leadership abilities and vast knowledge of equal employment laws culminated in her tenure as deputy associate administrator for Equal Opportunity Programs, a position she held for five years. Hall was one among the first African-American women to be appointed to the senior executive service of NASA. This photo was taken at Marshall during a Federal Women’s Week Luncheon on November 11, 1977 where Hall served as guest speaker.

Hall was known for saying, “You have to earn your wings every day.”

Sally Ride: Setting the Stage for Women in Space

The Astronaut Class of 1978, otherwise known as the “Thirty-Five New Guys,” was NASA’s first new group of astronauts since 1969. This class was notable for many reasons, including having the first African-American and first Asian-American astronauts and the first women.

Among the first women astronauts selected was Sally Ride. On June 18, 1983, Ride became the first American woman in space, when she launched with her four crewmates aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger on mission STS-7. On that day, Ride made history and paved the way for future explorers.

When those first six women joined the astronaut corps in 1978, they made up nearly 10 percent of the active astronaut corps. In the 40 years since that selection, NASA selected its first astronaut candidate class with equal numbers of women and men, and women now comprise 34 percent of the active astronauts at NASA.

Charlie Blackwell-Thompson: First Female Launch Director

As a part of our Artemis missions to return humans to the Moon and prepare for journeys to Mars, the Space Launch System, or SLS, rocket will carry the Orion spacecraft on an important flight test. Veteran spaceflight engineer Charlie Blackwell-Thompson will helm the launch team at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Her selection as launch director means she will be the first woman to oversee a NASA liftoff and launch team.

"A couple of firsts here all make me smile," Blackwell-Thompson said. "First launch director for the world's most powerful rocket — that's humbling. And I am honored to be the first female launch director at Kennedy Space Center. So many amazing women that have contributed to human space flight, and they blazed the trail for all of us.”

The Future of Women at NASA

In this image, NASA astronauts Anne McClain and Christina Koch pose for a portrait inside the Kibo laboratory module on the International Space Station. Both Expedition 59 flight engineers are members of NASA's 2013 class of astronauts.

As we move forward as a space agency, embarking on future missions to the Moon, Mars and beyond, we reflect on the women who blazed the trail and broke glass ceilings. Without their perseverance and determination, we would not be where we are today.

Follow Women@NASA for more stories like this one and make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Setting the Standards for Unmanned Aircraft

From advanced wing designs, through the hypersonic frontier, and onward into the era of composite structures, electronic flight controls, and energy efficient flight, our engineers and researchers have led the way in virtually every aeronautic development. And since 2011, aeronautical innovators from around the country have been working on our Unmanned Aircraft Systems integration in the National Airspace System, or UAS in the NAS, project.

This project was a new type of undertaking that worked to identify, develop, and test the technologies and procedures that will make it possible for unmanned aircraft systems to have routine access to airspace occupied by human piloted aircraft. Since the start, the goal of this unified team was to provide vital research findings through simulations and flight tests to support the development and validation of detect and avoid and command and control technologies necessary for integrating UAS into the NAS.

That interest moved into full-scale testing and evaluation to determine how to best integrate unmanned vehicles into the national airspace and how to come up with standards moving forward. Normally, 44,000 flights safely take off and land here in the U.S., totaling more than 16 million flights per year. With the inclusion of millions of new types of unmanned aircraft, this integration needs to be seamless in order to keep the flying public safe.

Working hand-in-hand, teams collaborated to better understand how these UAS's would travel in the national airspace by using NASA-developed software in combination with flight tests. Much of this work is centered squarely on technology called detect and avoid. One of the primary safety concerns with these new systems is the inability of remote operators to see and avoid other aircraft. Because unmanned aircraft literally do not have a pilot on board, we have developed concepts allowing safe operation within the national airspace.

In order to better understand how all the systems work together, our team flew a series of tests to gather data to inform the development of minimum operational performance standards for detect and avoid alerting guidance. Over the course of this testing, we gathered an enormous amount of data allowing safe integration for unmanned aircraft into the national airspace. As unmanned aircraft are becoming more ubiquitous in our world - safety, reliability, and proven research must coexist.

Every day new use case scenarios and research opportunities arise based around the hard work accomplished by this incredible workforce. Only time will tell how these new technologies and innovations will shape our world.

Want to learn the many ways that NASA is with you when you fly? Visit nasa.gov/aeronautics.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

-

jacobf123 liked this · 6 years ago

jacobf123 liked this · 6 years ago -

blintt reblogged this · 7 years ago

blintt reblogged this · 7 years ago -

blintt liked this · 7 years ago

blintt liked this · 7 years ago -

insteadingdotcom liked this · 8 years ago

insteadingdotcom liked this · 8 years ago -

kysanthree liked this · 8 years ago

kysanthree liked this · 8 years ago -

totoro2fab liked this · 9 years ago

totoro2fab liked this · 9 years ago -

voodoomon liked this · 9 years ago

voodoomon liked this · 9 years ago -

vibratingc0nd0ms liked this · 9 years ago

vibratingc0nd0ms liked this · 9 years ago -

loveismyenigma3141 reblogged this · 9 years ago

loveismyenigma3141 reblogged this · 9 years ago -

loveismyenigma3141 liked this · 9 years ago

loveismyenigma3141 liked this · 9 years ago -

colourmoichic reblogged this · 9 years ago

colourmoichic reblogged this · 9 years ago -

thesasquatchgirl liked this · 9 years ago

thesasquatchgirl liked this · 9 years ago -

aegistheia reblogged this · 9 years ago

aegistheia reblogged this · 9 years ago -

smallpercentage liked this · 9 years ago

smallpercentage liked this · 9 years ago -

bohemiasinbar reblogged this · 9 years ago

bohemiasinbar reblogged this · 9 years ago -

235uzy reblogged this · 9 years ago

235uzy reblogged this · 9 years ago -

crabapplecove liked this · 9 years ago

crabapplecove liked this · 9 years ago -

distracted-deriving reblogged this · 9 years ago

distracted-deriving reblogged this · 9 years ago -

reasonsforreason reblogged this · 9 years ago

reasonsforreason reblogged this · 9 years ago -

iliana-b reblogged this · 9 years ago

iliana-b reblogged this · 9 years ago -

minervamaga reblogged this · 9 years ago

minervamaga reblogged this · 9 years ago -

yikesitjenna liked this · 9 years ago

yikesitjenna liked this · 9 years ago -

transvoidspace liked this · 9 years ago

transvoidspace liked this · 9 years ago -

wolf-government reblogged this · 9 years ago

wolf-government reblogged this · 9 years ago -

freelancer-kentucky reblogged this · 9 years ago

freelancer-kentucky reblogged this · 9 years ago -

freelancer-kentucky liked this · 9 years ago

freelancer-kentucky liked this · 9 years ago -

agentnavi reblogged this · 9 years ago

agentnavi reblogged this · 9 years ago -

metalmanatee liked this · 9 years ago

metalmanatee liked this · 9 years ago -

ashynarr reblogged this · 9 years ago

ashynarr reblogged this · 9 years ago -

lukesreys reblogged this · 9 years ago

lukesreys reblogged this · 9 years ago -

fuuei liked this · 9 years ago

fuuei liked this · 9 years ago -

kanirou-crosshack reblogged this · 9 years ago

kanirou-crosshack reblogged this · 9 years ago -

pardon-my-scifi reblogged this · 9 years ago

pardon-my-scifi reblogged this · 9 years ago -

pardon-my-scifi liked this · 9 years ago

pardon-my-scifi liked this · 9 years ago

Explore the universe and discover our home planet with the official NASA Tumblr account

1K posts