Wee Kirk O’ The Heather Wedding Chapel, Las Vegas (1940-2020)

Wee Kirk o’ the Heather Wedding Chapel, Las Vegas (1940-2020)

Photo: Undated, mid 50s. ‘51 Studebaker.

This was an adobe home built in the mid 20s at 213 South 5th Street, later 231 Las Vegas Blvd S. When U.S. Route 91 connected through Las Vegas via 5th St in the late 20s, chapels, motels, and other businesses catering to tourists opened along the road.

Mrs. J. Edwards Webb began performing wedding ceremonies in her front room either in the late 30s or early 40s. It came to be known as Webb’s Wedding Chapel and/or Wee Kirk o’ the Heather. According to the chapel when they were still open, “The city decided they needed a business license, so in 1940 they got a license and chose the name Wee Kirk.”

The earliest reference we can find to “Wee Kirk” is a listing in the RJ, 5/5/41. The name might come from the popular Wee Kirk o’ the Heather in Glendale CA, built in the 20s as a replica of a 17th century church in Scotland.

Wee Kirk was modified in the 50s: a steeple was added to the top of the building and the front room was enlarged. Nearby Graceland Chapel aka Gretna Green also started as a home, was converted into a chapel in the same era as Wee Kirk with similar modifications made in the 50s.

Wee Kirk's original sign was remade with neon at some time in the late 40s or early 50s. It was and replaced in the 70s or 80s with a signboard seen in the ‘84 photo below.

Wee Kirk closed during the 2020 pandemic and was demolished 10/3/2020.

Undated circa '40-'43. L.F. Manis Collection, UNLV Special Collections & Archives.

Circa '44

Postcards, circa 40s

Undated photo c. '50

Postcard, circa 60s – with the steeple

4/18/84 – Photo by Jane Kowalewski. Clark County Historic Property, Wee Kirk O' the Heather Wedding Chapel, Nevada State Museum, Las Vegas.

More Posts from Slim-k-d and Others

It's an open notes test and some dense motherfuckers still can't figure out the answers.

Item: big jar of serotonin

Life changes fast. Life changes in the instant. You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends. The question of self-pity. “At some point, in the interest of remembering what seemed most striking about what had happened, I considered adding those words, ´the ordinary instant.´ I saw immediately that there would be no need to add the word "ordinary,” because there would be no forgetting it: the word never left my mind. It was in fact the ordinary nature of everything preceding the event that prevented me from truly believing it had happened, absorbing it, incorporating it, getting past it. I recognize now that there was nothing unusual in this: confronted with sudden disaster, we all focus on how unremarkable the circumstances were in which the unthinkable occurred, the clear blue sky from which the plane fell, the routine errand that ended on the shoulder with the car in flames, the swings where the children were playing as usual when the rattlesnake struck from the ivy.“ After Life , by Joan Didion. The best text I have ever read about death, the unpredictability of life, and grief.

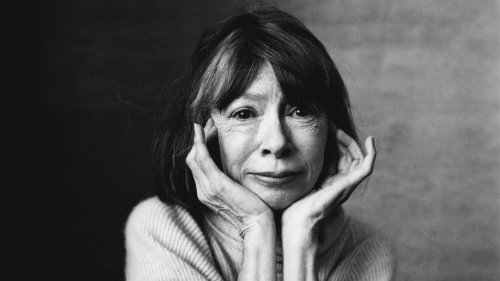

Once, in a dry season, I wrote in large letters across two pages of a notebook that innocence ends when one is stripped of the delusion that one likes oneself. Although now, some years later, I marvel that a mind on the outs with itself should have nonetheless made painstaking record of its every tremor, I recall with embarrassing clarity the flavor of those particular ashes. It was a matter of misplaced self-respect. I had not been elected to Phi Beta Kappa. This failure could scarcely have been more predictable or less ambiguous (I simply did not have the grades), but I was unnerved by it; I had somehow thought myself a kind of academic Raskolnikov, curiously exempt from the cause-effect relationships that hampered others. Although the situation must have had even then the approximate tragic stature of Scott Fitzgerald’s failure to become president of the Princeton Triangle Club, the day that I did not make Phi Beta Kappa nevertheless marked the end of something, and innocence may well be the word for it. I lost the conviction that lights would always turn green for me. Although to be driven back upon oneself is an uneasy affair at best, rather like trying to cross a border with borrowed credentials, it seems to me now the one condition necessary to the beginnings of real self-respect. Most of our platitudes notwithstanding, self-deception remains the most difficult deception. The charms that work on others count for nothing in that devastatingly well-lit back alley where one keeps assignations with oneself: no winning smiles will do here, no prettily drawn lists of good intentions.The dismal fact is that self-respect has nothing to do with the approval of others—who are, after all, deceived easily enough. To do without self-respect, on the other hand, is to be an unwilling audience of one to an interminable home movie that documents one’s failings, both real and imagined, with fresh footage spliced in for each screening. To live without self-respect is to lie awake some night, beyond the reach of warm milk, phenobarbital, and the sleeping hand on the coverlet, counting up the sins of commission and omission, the trusts betrayed, the promises subtly broken, the gifts irrevocably wasted through sloth or cowardice or carelessness. However long we postpone it, we eventually lie down alone in that notoriously un- comfortable bed, the one we make ourselves. Whether or not we sleep in it depends, of course, on whether or not we respect ourselves. There is a common superstition that “self-respect” is a kind of charm against snakes, something that keeps those who have it locked in some unblighted Eden, out of strange beds, ambivalent conversations, and trouble in general. It does not at all. It has nothing to do with the face of things, but concerns instead a separate peace, a private reconciliation. People with self-respect have the courage of their mistakes. They know the price of things. In brief, people with self-respect exhibit a certain toughness, a kind of moral nerve; they display what was once called character, a quality which, although approved in the abstract, sometimes loses ground to other, more instantly negotiable virtues. Nonetheless, character — the willingness to accept responsibility for one’s own life — is the source from which self-respect springs. To have that sense of one’s intrinsic worth which, for better or for worse, constitutes self-respect, is potentially to have everything: the ability to discriminate, to love and to remain indifferent. To lack it is to be locked within oneself, paradoxically incapable of either love or indifference. If we do not respect ourselves, we are on the one hand forced to despise those who have so few resources as to consort with us, so little perception as to remain blind to our fatal weaknesses. On the other, we are peculiarly in thrall to everyone we see, curiously determined to live out—since our self-image is untenable—their false notions of us. We flatter ourselves by thinking this compulsion to please others an attractive trait: a gift for imaginative empathy, evidence of our willingness to give. At the mercy of those we can not but hold in contempt, we play roles doomed to failure before they are begun, each defeat generating fresh despair at the necessity of divining and meeting the next demand made upon us. It is the phenomenon sometimes called alienation from self. In its advanced stages, we no longer answer the telephone, because someone might want something; that we could say no without drowning in self-reproach is an idea alien to this game. Every encounter demands too much, tears the nerves, drains the will, and the spectre of something as small as an unanswered letter arouses such disproportionate guilt that one’s sanity becomes an object of speculation among one’s acquaintances. To assign unanswered letters their proper weight, to free us from the expectations of others, to give us back to ourselves—there lies the great, the singular power of self-respect. Without it, one eventually discovers the final turn of the screw: one runs away to find oneself, and finds no one at home. In memory of the great Joan Didion: On Self-Respect.

"As one reads history, not in the expurgated editions written for school-boys and passmen, but in the original authorities of each time, one is absolutely sickened, not by the crimes that the wicked have committed, but by the punishments that the good have inflicted; and a community is infinitely more brutalised by the habitual employment of punishment, than it is by the occurrence of crime. It obviously follows that the more punishment is inflicted the more crime is produced, and most modern legislation has clearly recognised this, and has made it its task to diminish punishment as far as it thinks it can. Wherever it has really diminished it, the results have always been extremely good. The less punishment, the less crime. When there is no punishment at all, crime will either cease to exist, or, if it occurs, will be treated by physicians as a very distressing form of dementia, to be cured by care and kindness. For what are called criminals nowadays are not criminals at all. Starvation, and not sin, is the parent of modern crime."

~ Oscar Wilde, The Soul of Man Under Socialism, 1891. Just a few short years before his own imprisonment, which ultimately lead to his death.

-

slim-k-d reblogged this · 1 month ago

slim-k-d reblogged this · 1 month ago -

slim-k-d liked this · 1 month ago

slim-k-d liked this · 1 month ago -

missugarpie reblogged this · 1 month ago

missugarpie reblogged this · 1 month ago -

twoseparatecoursesmeet liked this · 1 month ago

twoseparatecoursesmeet liked this · 1 month ago -

guennyboy6137-love reblogged this · 1 month ago

guennyboy6137-love reblogged this · 1 month ago -

guennyboy6137-love liked this · 1 month ago

guennyboy6137-love liked this · 1 month ago -

chester40 reblogged this · 2 months ago

chester40 reblogged this · 2 months ago -

here4-sims4 reblogged this · 2 months ago

here4-sims4 reblogged this · 2 months ago -

blackandwhite24k liked this · 2 months ago

blackandwhite24k liked this · 2 months ago -

ikabod liked this · 2 months ago

ikabod liked this · 2 months ago -

omarayusosbrows liked this · 2 months ago

omarayusosbrows liked this · 2 months ago -

omarayusosbrows reblogged this · 2 months ago

omarayusosbrows reblogged this · 2 months ago -

homeatlast reblogged this · 2 months ago

homeatlast reblogged this · 2 months ago -

lawndaleclub liked this · 2 months ago

lawndaleclub liked this · 2 months ago -

djzabu reblogged this · 2 months ago

djzabu reblogged this · 2 months ago -

route22ny liked this · 2 months ago

route22ny liked this · 2 months ago -

detroitlib liked this · 2 months ago

detroitlib liked this · 2 months ago -

nightjasmine10 liked this · 2 months ago

nightjasmine10 liked this · 2 months ago -

knitty-perrine reblogged this · 2 months ago

knitty-perrine reblogged this · 2 months ago -

teaceremonial reblogged this · 2 months ago

teaceremonial reblogged this · 2 months ago -

teaceremonial liked this · 2 months ago

teaceremonial liked this · 2 months ago -

chaplinfortheages liked this · 2 months ago

chaplinfortheages liked this · 2 months ago -

saturnbees liked this · 2 months ago

saturnbees liked this · 2 months ago -

slickcycle liked this · 2 months ago

slickcycle liked this · 2 months ago -

myworldinloveandshame liked this · 2 months ago

myworldinloveandshame liked this · 2 months ago -

hillbillyholly reblogged this · 2 months ago

hillbillyholly reblogged this · 2 months ago -

hillbillyholly liked this · 2 months ago

hillbillyholly liked this · 2 months ago -

facslvr liked this · 2 months ago

facslvr liked this · 2 months ago -

sins1987 liked this · 2 months ago

sins1987 liked this · 2 months ago -

whiskeyandbingo liked this · 2 months ago

whiskeyandbingo liked this · 2 months ago -

scisanta25 liked this · 2 months ago

scisanta25 liked this · 2 months ago -

bluplaid liked this · 2 months ago

bluplaid liked this · 2 months ago -

vegasgirl16 liked this · 2 months ago

vegasgirl16 liked this · 2 months ago -

jinxysmidcentury reblogged this · 2 months ago

jinxysmidcentury reblogged this · 2 months ago -

jinxysmidcentury liked this · 2 months ago

jinxysmidcentury liked this · 2 months ago -

vampiremother liked this · 2 months ago

vampiremother liked this · 2 months ago -

stylecouncil liked this · 2 months ago

stylecouncil liked this · 2 months ago -

sleevesontrees reblogged this · 2 months ago

sleevesontrees reblogged this · 2 months ago -

bigcupofwater liked this · 2 months ago

bigcupofwater liked this · 2 months ago -

savethelifeofmychild reblogged this · 2 months ago

savethelifeofmychild reblogged this · 2 months ago -

torksmiths reblogged this · 2 months ago

torksmiths reblogged this · 2 months ago -

wearenemies liked this · 2 months ago

wearenemies liked this · 2 months ago -

cnythuk1 reblogged this · 2 months ago

cnythuk1 reblogged this · 2 months ago -

8one6 liked this · 2 months ago

8one6 liked this · 2 months ago -

crick-crack-the-kitkat liked this · 2 months ago

crick-crack-the-kitkat liked this · 2 months ago -

faggot-hell reblogged this · 2 months ago

faggot-hell reblogged this · 2 months ago -

faggot-hell liked this · 2 months ago

faggot-hell liked this · 2 months ago