Hello There, Hope You're Having A Nice Day

hello there, hope you're having a nice day <3

so i've been reading a lot of fics lately, uk for sanity's sake, and i've noticed that in most of them, lwj doesn't use contractions (eg., says do not instead of don't)?? and i think he doesn't in the novel either but i don't remember lol so i can't be sure but anyway that made me curious - does chinese have contractions as well? does he not use it bc it's informal?

hello there! I’m doing all right, i started to answer this ask while waiting for a jingyeast loaf to come out of the oven 😊 many thanks to @bookofstars for helping me look over/edit/correct this post!! :D

anyways! the answer to your questions are complicated (of course it is when is anything simple with me), so let’s see if I can break it down--you’re asking a) whether chinese has contractions, b) if it does, how does they change the tone of the sentence--is it similar to english or no?, and c) how does this all end up with lan wangji pretty much never using contractions in english fic/translation?

I’m gonna start by talking about how formality is (generally) expressed in each language, and hopefully, by the end of this post, all the questions will have been answered in one way or another. so: chinese and english express variations in formality/register differently, oftentimes in ways that run contrary to one another. I am, as always, neither a linguist nor an expert in chinese and english uhhh sociological grammar? for lack of a better word. I’m speaking from my own experience and knowledge :D

so with a character like lan wangji, it makes perfect sense in english to write his dialogue without contractions, as contractions are considered informal or colloquial. I don’t know if this has changed in recent years, but I was always taught in school to never use contractions in my academic papers.

However! not using contractions necessarily extends the length of the sentence: “do not” takes longer to say than “don’t”, “cannot” is longer than “can’t” etc. in english, formality is often correlated with sentence length: the longest way you can say something ends up sounding the most formal. for a very simplified example, take this progression from least formal to absurdly formal:

whatcha doin’?

what’re you doing?

what are you doing? [standard colloquial]

may I ask what you are doing?

might I inquire as to what you are doing?

excuse me, but might I inquire as to what you are doing?

pardon my intrusion, but might I inquire as to what you are doing?

please pardon my intrusion, but might inquire as to the nature of your current actions?

this is obviously a somewhat overwrought example, but you get the point. oftentimes, the longer, more complex, more indirect sentence constructions indicate a greater formality, often because there is a simultaneous decreasing of certainty. downplaying the speaker’s certainty can show deference (or weakness) in english, while certainty tends to show authority/confidence (or aggression/rudeness).

different words also carry different implications of formality—in the example, I switched “excuse me” to “pardon me” during one of the step ups. pardon (to me at least) feels like a more formal word than “excuse”. Similarly, “inquire” is more formal than “ask” etc. I suspect that at least some of what makes one word seem more formal than one of its synonyms has to do with etymology. many of english’s most formal/academic words come from latin (which also tends to have longer words generally!), while our personal/colloquial words tend to have germanic origins (inquire [latin] vs ask [germanic]).

you’ll also notice that changing a more direct sentence structure (“may I ask what”) to a more indirect one (“might I inquire as to”) also jumps a register. a lot of english is like this — you can complicate simple direct sentences by switching the way you use the verbs/how many auxiliaries you use etc.

THE POINT IS: with regards to english, more formal sentence structures are often (not always) longer and more indirect than informal ones. this leads us to a problem with a character like lan wangji.

lan wangji is canonically very taciturn. if he can express his meaning in two words rather than three, then he will. and chinese allows for this—in extreme ways. if you haven’t already read @hunxi-guilai’s post on linguistic register (in CQL only, but it’s applicable across the board), I would start there because haha! I certainly do Not have a degree in Classical Chinese lit and she does a great job. :D

you can see from the examples that hunxi chose that often, longer sentences tend to be more informal in chinese (not always, which I’ll circle back to at the end lol). Colloquial chinese makes use of helping particles to indicate tone and meaning, as is shown in wei wuxian’s dialogue. and, as hunxi explained, those particles are largely absent from lan wangji’s speech pattern. chinese isn’t built of “words” in the way English is—each character is less a word and more a morpheme—and the language allows for a lot of information to be encoded in one character. a single character can often stand for a phrase within a sentence without sacrificing either meaning or formality. lan wangji makes ample use of this in order to express himself in the fewest syllables possible.

so this obviously leads to an incongruity when trying to translate his dialogue or capture his voice in English: shorter sentences are usually more direct by nature, and directness/certainty is often construed as rudeness -- but it might seem strange to see lan wangji’s dialogue full of longer sentences while the narration explicitly says that he uses very short sentences. so what happens is that many english fic writers extrapolated this into creating an english speech pattern for lan wangji that reads oddly. they’ll have lan wangji speak in grammatically incoherent fragments that distill his intended thought because they’re trying to recreate his succinctness. unfortunately, English doesn’t have as much freedom as Chinese does in this way, and it results in lan wangji sounding as if he has some kind of linguistic impediment and/or as if he’s being unspeakably rude in certain situations. In reality, lan wangji’s speech is perfectly polite for a young member of the gentry (though he’s still terribly rude in other ways lol). he speaks in full, and honestly, quite eloquent sentences.

hunxi’s post already has a lot of examples, but I figure I’ll do one as well focused on the specifics of this post.

I’m going to use this exchange from chapter 63 between the twin jades because I think it’s a pretty simple way to illustrate what I’m talking about:

蓝曦臣道:“你亲眼所见?”

蓝忘机道:“他亲眼所见。”

蓝曦臣道:“你相信他?”

蓝忘机道:“信。”

[...] 蓝曦臣道:“那么金光瑶呢?”

蓝忘机道:“不可信。”

my translation:

Lan Xichen said, “You saw it with your own eyes?”

Lan Wangji said, “He saw it with his own eyes.”

Lan Xichen said, “You believe him?”

Lan Wangji said, “I believe him.”

[...] Lan Xichen said, “Then what about Jin Guangyao?”

Lan Wangji said, “He cannot be believed.”

you can see how much longer the (pretty literal) english translations are! every single line of dialogue is expanded because things that can be omitted in chinese cannot be omitted in english without losing grammatical coherency. i‘ll break a few of them down:

Lan Xichen’s first line:

你 (you) 亲眼 (with one’s own eyes) 所 (literary auxiliary) 见 (met/saw)?

idk but i love this line a lot lmao. it just has such an elegant feel to me, probably because I am an uncultured rube. anyways, you see here that he expressed his full thought in five characters.

if I were to rewrite this sentence into something much less formal/much more modern, I might have it become something like this:

你是自己看见的吗?

你 (you) 是 (to be) 自己 (oneself) 看见 (see) 的 (auxiliary) 吗 (interrogative particle)?

i suspect that this construction might even be somewhat childish? I’ve replaced every single formal part of the sentence with a more colloquial one. instead of 亲眼 i’ve used 自己, instead of 所见 i’ve used 看见的 and then also added an interrogative particle at the end for good measure (吗). To translate this, I would probably go with “Did you see it yourself?”

contained in this is also an example of how one character can represent a whole concept that can also be represented with two characters: 见 vs 看见. in this example, both mean “to see”. we’ll see it again in the next example as well:

in response to lan xichen’s, “you believe him?” --> 你 (you) 相信 (believe) 他 (him)? lan wangji answers with, “信” (believe).

chinese does not do yes or no questions in the same way that english does. there is no catch-all for yes or no, though there are general affirmative (是/有) and negative (不/没) characters. there are other affirmative/negative characters, but these are the ones that I believe are the most common and also the ones that you may see in response to yes or no questions on their own. (don’t quote me on that lol)

regardless, the way you respond to a yes or no question is often by repeating the verb phrase either in affirmative or negative. so here, when lan xichen asks if lan wangji believes wei wuxian, lan wangji responds “believe”. once again, you can see that one character can stand in for a concept that may also be expressed in two characters: 信 takes the place of 相信. lan wangji could have responded with “相信” just as well, but, true to his character, he didn’t because he didn’t need to. this is still a complete sentence. lan wangji has discarded the subject (I), the object (him), and also half the verb (相), and lost no meaning whatsoever. you can’t do this in english!

and onto the last exchange:

lan xichen: 那么 (then) 金光瑶 (jin guangyao) 呢 (what about)?

lan wangji: 不可 (cannot) 信 (believe)

you can actually see the contrast between the two brothers’ speech patterns even in this. lan xichen’s question is not quite as pared down as it could be. if it were wangji’s line instead, I would expect it to read simply “金光瑶呢?” which would just be “what about jin guangyao?” 那么 isn’t necessary to convey the core thought -- it’s just as how “then what about” is different than “what about”, but “then” is not necessary to the central question. if we wanted to keep the “then” aspect, you could still cut out 么 and it would be the same meaning as well.

a FINAL example of how something can be cut down just because I think examples are helpful:

“I don’t know” is usually given as 我不知道. (this is what nie huaisang says lol) It contains subject (我) and full verb (知道). you can pare this straight down to just 不知 and it would mean the same thing in the correct context. i think most of the characters do this at least once? it sounds more literary -- i don’t know that i would ever use it in everyday speech, but the fact remains that it’s a possibility. both could be translated as “I do not know” and it would be accurate.

ANYWAYS, getting all the way back to one of your original questions: does chinese have contractions? and the answer is like... kind of...?? but not really. there’s certainly slang/dialect variants that can be used in ways that are reminiscent of english contractions. the example I’m thinking of is the character 啥 (sha2) which can be used as slang in place of 什么 (shen2 me). (which means “what”)

so for a standard sentence of, 你在做什么? (what are you doing), you could shorten down to just 做啥? and the second construction is less formal than the first, but they mean the same thing.

other slang i can think of off the top of my head: 干嘛 (gan4 ma2) is also informal slang for “what are you doing”. and i think this is a regional thing, but you can also use 搞 (gao3) and 整 (zheng3) to mean “do” as well.

so in the same way that you can replace 什么 with 啥, you can replace 做 as well to get constructions like 搞啥 (gao3 sha2) and 整啥 (zheng3 sha2).

these are all different ways to say “what are you doing” lmao, and in this case, shorter is not, in fact, more formal.

woo! we made it to the end! I hope it was informative and helpful to you anon. :D

this is where I would normally throw my ko-fi, but instead, I’m actually going to link you to this fundraising post for an old fandom friend of mine. her house burned down mid-september and they could still use help if anyone can spare it! if this post would have moved you to buy me a ko-fi, please send that money to her family instead. :) rbs are also appreciated on the post itself. (* ´▽` *)

anyways, here’s the loaf jingyeast made :3 it was very tasty.

More Posts from Weishenmewwx and Others

The Husky and His White Cat ShiZun, volume TWO 2 二

(The one with the very pale cover)

(English 7Seas version) Notes 3 of 4

Pages 208-327

More under the cut.

Back to my Masterlist.

So you saw the trailer and thought you come to The Lost Tomb Reboot to see them raiding tombs, fighting ghosts, killing monsters, exploding this exploding that...

Turns out you see two 40-ish dudes talking nonsense, waving fake lightsabers in a tomb (yeah, in a tomb, no less) 🙄 And in later episodes they’re gonna dance tango, sing karaoke and hula hoop, also in a tomb...

I’m sorry not sorry I set all the wrong expectation...

[Okay I’m kidding, they actually do raid tombs, kill monsters, explode things. But it isn’t my fault our main characters happen to be idiots... ( ・ᴗ・̥̥̥ )]

MDZS Vol 5 Annotations 5

Part 5 of 6, pages 343 - 375

Helllo again! I love these Extras.

Here are a few places where I got tripped up in my reading — all minor adjustments to vocabulary or word order or dumb clarification for my sake because something felt ambiguous in English:

They’re just melting it.

More under the cut.

Not that you need to learn more Chinese time-system / ordinal-ranking stuff, but here it is if you’re interested: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heavenly_Stems

When I first read “bodies strewn across the ground” I freaked out thinking that I had somehow missed a MDZS Extra about some terrible massacre; then I realized that in Chinese, there is a nice distinction between flesh bodies that are probably living, 肉体, and corpses 尸体; whereas in English it’s all just “bodies.” 🙁

MDZS Masterlist.

All the Books I'm Annotating Masterlist.

how lan xichen says lan zhan’s name: ʷᵃⁿᵍʲⁱ

how wei wuxian says lan zhan’s name: 𝙇𝘼𝙉 𝙕𝙃𝘼𝙉

how lan zhan says wei wuxian’s name: 𝔀𝓮𝓲 𝔂𝓲𝓷𝓰

how jiang cheng says wei wuxian’s name: ẅ̷̛͚͔̟͓̜̯̮̹̞̊̌̏̍́̏̐e̴̢̜͎͚̝̘̿͛͒̔̏̈́͑̏̊͜i̴̩͎͓͒̐̔̍͌̀͌͝ ̸̘̳̀̈̈́w̶̧̻͑̅͂̇ù̸̡̝͖̤̙̯͍̾̂̈́͜ẋ̴̢̡̛̰̥̳̱̯̠͕̀i̶̺̟̒̊̕à̶̛̗͓̋̑̏̿̃͗͌n̴͙͇͍̯̂̕

I finally found an English-Language explanation of What Happened in the novel 镇魂 Guardian by Priest! It had been hidden in video…and I had refused to watch any reviews until I had finished watching the drama…

So! If you happen to be as confused as I was after reading (loving!)(confused loving!) Zhen Hun, here’s another person to commiserate with about how unfathomable (illogical) the plot of the novel truly is (but we still don’t care. We just want more WeiLan).

https://youtu.be/jfOH0kFvDuQ

Stars of Chaos 杀破狼

Vol 2, Notes 7, pages 339 - 366.

Another eight notes...

The idiom for "too late" in Chinese is 黄花菜都凉了 "The Yellow Lilly (chrysanthemum? Yellow lily?) dish is already cold", which I had to look up.

Apparently, there was a time and place in ancient China where, when the fancy nobles would throw a banquet, they would serve 黄花菜 as the final dish. If you delayed attending so long that the 黄花菜 was already cold, then you had completely missed the banquet. You were too late.

牲口 is, technically, "draught animal" or "beast of burden," but I'm pretty sure what Priest means here is "those cold-blooded war beasts."

top: I think of it as two separate, unrelated, consecutive actions.

bottom: 铁膝飞足, iron knees flying feet, is so easy to read in Chinese. (This is the first time I've ever seen the word "poleyns.")

top: "young and inexperienced" in Chinese here is 初出茅庐, "first time out of the thatched cottage."

初出茅庐 is the coolest little idiom. So, in the Three Kingdoms period, there was a scholar called Zhuge Liang. Liu Bei, leader of the Shu Han, begged Zhuge Liang to become his advisor and, after three visits, Zhuge Liang agreed. This was the first time that Zhuge Liang accepted such an advisory position, and the "first time" that he left his thatched cottage (it was wartime. There was a lot of travel involved with advising a king/warlord).

Anyway, Zhuge Liang was a genius and immediately won a lot of battles through superior strategy.

next: for "dig in his heels before the capital," I feel like that could be more clearly written as "hold the capital."

next: regarding "unsalvageable situation," he's talking about his relationship with the emperor.

last: "No eggs remain when the nest overturns" is a common idiom, 覆巢之下无完卵。 We're all in it together.

"running to the market" 赶集 is a way to describe how things are noisy and busy and people are running back and forth (not bright and merry with people buying gifts for each other).

I think... the indescribable smell is the mix of gunpowder and blood...

If you don't know already, the Origin Myth for Where Humans Come From is that the half-snake goddess Nuwa made humans out of clay :)

I'm not sure why, but in English I thought that one of the Western soldiers was laughing; but in Chinese it's really clear that none of the soldiers are laughing.

Four more...

My DanMei Literary Adventure Masterpost

Stars of Chaos - All Notes Links

Thank you, @anambermusicbox !

September 29 Day Countdown (6/29): 2019/02/19 Global Chinese Golden Chart 《流行音乐全金榜》 Live Broadcasted Radio Interview on Dragonfly FM

Highlights:

(14:15) Interviewer talks about how Zhou Shen’s activity on Weibo is completely unlike a celebrity; Zhou Shen mentions that Gao Xiaosong says he’s never acted like a celebrity and often tells him: “Zhou Shen, you’ve already debuted for so many years, how is it that you actually behave less and less like a celebrity?”

(21:40) “What are Shengmi to you?”:

Zhou Shen: They’re an inexplicable existence. Because, I’ve told them so many times, that I’ve always never understood what motivates them—not only my shengmi, but even just fans in general—what motivates them to support their favourite singer or idol. I feel like, personally, I can’t do much for them. All I can really do is sing some songs. […] I feel at a loss; I feel like I have no way to guarantee something good to repay them for their continuous support, for their love. Because I’m a really insecure person, and yet they’re able to give such an insecure person some sense of security… you can imagine how great their strength is.

(26:45) Interviewer asks if Zhou Shen has a 小名 (family nickname):

Zhou Shen: Because 深 and 星 are pronounced exactly the same in hunanese, my family has always called me Xingxing. When getting me registered, they asked the person doing the registration to register “our family’s Xingxing”, and the person said “okay, and your family name is Zhou,” so they literally registered me as “Zhou Xingxing” (周星星) (*Interviewer laughs*).

[I didn’t know this was my original legal name] until my high school entrance exam, when they called out “Zhou Xingxing” during rollcall, and no one responded. They thought it must’ve been a typo at first, because when they called the name out, the entire class was like “HAHAHAHAHA WHO THE HECK IS NAMED THAT”, and I was also there laughing like “HAHAHAHAHA WHO THE HECK IS NAMED THAT” (*laughs*) And then after everyone was called, they asked whether there was anyone who hadn’t been called. I said “I haven’t” and they said “Okay this must be you”, then everyone was like “HAHAHAHAHA YOU’RE ZHOU XINGXING” […] Afterwards, I went and legally changed my name back to Zhou Shen.

Keep reading

Wei Wuxian | Ep. 11

for @/the-lady-of-the-blue

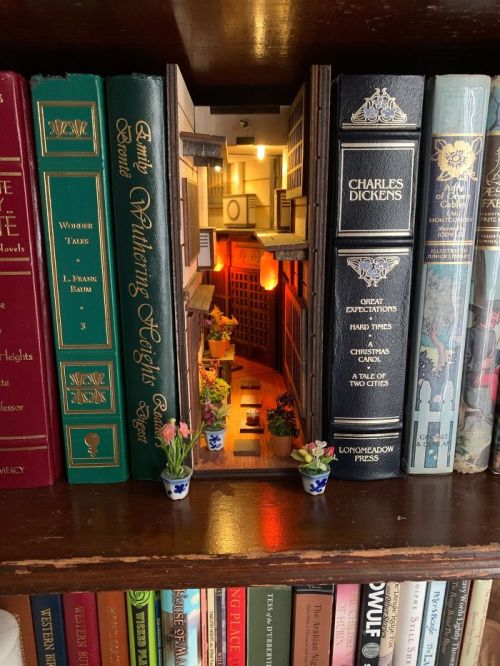

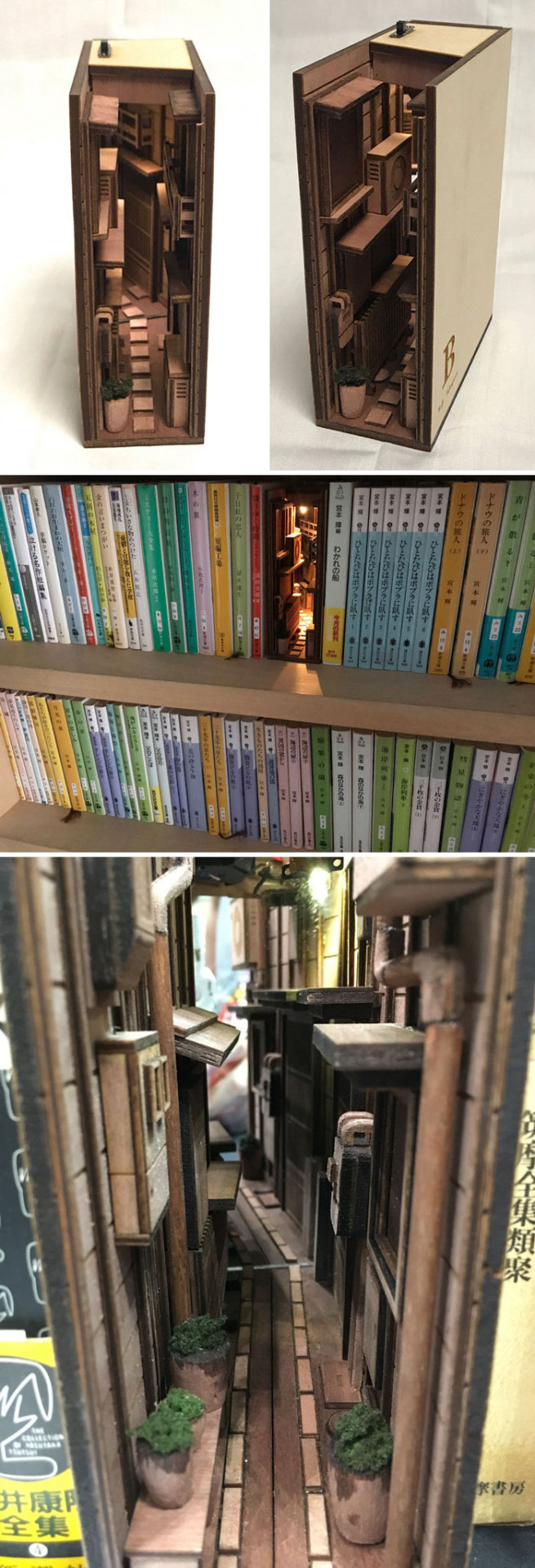

Bookshelf inserts

hey say that you can’t judge a book by its cover. But what if the cover alone can tell you the whole story? Welcome to the world of book nooks where creativity runs wild!

These hand-made creations will draw you into tiny places of wonder: from the hobbit hole to the Blade Runner-inspired apocalyptic alley or Lord of the Rings-themed door replica equipped with motion sensors.

This book nook my mother got on Ebay

A Magical bookshop in your own bookshelf

I made a booknook for a christmas gift, my inspiration was Blade Runner. It’s 11" X 6"

Not only are book nook inserts a fun way to train your creativity muscle, they can also be a solution to making reading great again. A recent study done by Pew Research Center showed that a staggering quarter of American adults don’t read books in any shape or form. The same study suggested that the likelihood of reading was directly linked to wealth and educational level. Add high levels of modern insomnia and full-time employment that leaves many of us drained at the end of the day, and the idea of opening a book seems unappealing, to say the least.

Now imagine yourself walking past a bookshelf full of these mini worlds—the dioramas of an alley. They catch your attention and you cannot help but see what’s inside. The pioneer of the book nook concept is the Japanese artist Monde. Monde introduced his creations to the Design Festa in 2018 and received overwhelming feedback. 178K likes on twitter later, Monde has become an inspiration to the aspiring arts and crafts lovers who join on r/booknooks to share their spectacular ideas.

Hobbit Hole

Design, print and paint a small shelf to decorate shelves

worlds hidden in a bookcase

A double wide endor inspired wilderness piece

Old Italy book nook

Diagon Alley booknook

Witch is watching you

Warhammer-style booknook

Creature from the Black Lagoon bookshelf monster

A booknook inspired by Les Miserables

source https://www.boredpanda.com/book-nook-shelf-inserts

I love this so much, thank you!😊❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️

Links are updated!

I finally connected and updated links between my Notes pages for Stars of Chaos!

Stars of Chaos - All The Notes List

All The Seven Seas Books Masterlist

I hope you enjoy them and find them useful.

And let me know if anyone wants an Audio Guide to the names, like I did for Erha.

:)

-

kkimbly liked this · 4 months ago

kkimbly liked this · 4 months ago -

elrondsscribe reblogged this · 4 months ago

elrondsscribe reblogged this · 4 months ago -

somefapmaterial liked this · 5 months ago

somefapmaterial liked this · 5 months ago -

snarkissist liked this · 6 months ago

snarkissist liked this · 6 months ago -

raindropcastles liked this · 6 months ago

raindropcastles liked this · 6 months ago -

word-salad reblogged this · 7 months ago

word-salad reblogged this · 7 months ago -

lion-writer reblogged this · 7 months ago

lion-writer reblogged this · 7 months ago -

lion-writer liked this · 7 months ago

lion-writer liked this · 7 months ago -

matsinko liked this · 8 months ago

matsinko liked this · 8 months ago -

edenrain97 liked this · 8 months ago

edenrain97 liked this · 8 months ago -

crazybee liked this · 8 months ago

crazybee liked this · 8 months ago -

viskii404 liked this · 8 months ago

viskii404 liked this · 8 months ago -

word-salad liked this · 9 months ago

word-salad liked this · 9 months ago -

greetings-gremlins liked this · 10 months ago

greetings-gremlins liked this · 10 months ago -

roxyroxqueen-blog reblogged this · 10 months ago

roxyroxqueen-blog reblogged this · 10 months ago -

roxyroxqueen-blog liked this · 10 months ago

roxyroxqueen-blog liked this · 10 months ago -

br0therw1fe reblogged this · 1 year ago

br0therw1fe reblogged this · 1 year ago -

yaoimongerer liked this · 1 year ago

yaoimongerer liked this · 1 year ago -

bookwormsontherun liked this · 1 year ago

bookwormsontherun liked this · 1 year ago -

exhausted-pigeon liked this · 1 year ago

exhausted-pigeon liked this · 1 year ago -

whomeidontknowthem liked this · 1 year ago

whomeidontknowthem liked this · 1 year ago -

travalerray reblogged this · 1 year ago

travalerray reblogged this · 1 year ago -

travalerray liked this · 1 year ago

travalerray liked this · 1 year ago -

disgruntledkittycat liked this · 1 year ago

disgruntledkittycat liked this · 1 year ago -

aescyra liked this · 1 year ago

aescyra liked this · 1 year ago -

opalescentgold liked this · 1 year ago

opalescentgold liked this · 1 year ago -

exerciseinexposure reblogged this · 1 year ago

exerciseinexposure reblogged this · 1 year ago -

dogbollocks liked this · 1 year ago

dogbollocks liked this · 1 year ago -

lwjsheadband liked this · 1 year ago

lwjsheadband liked this · 1 year ago -

xxbreak liked this · 1 year ago

xxbreak liked this · 1 year ago -

secretlyatimelady liked this · 1 year ago

secretlyatimelady liked this · 1 year ago -

1fsh-2fsh-redfsh-blufsh reblogged this · 1 year ago

1fsh-2fsh-redfsh-blufsh reblogged this · 1 year ago -

1fsh-2fsh-redfsh-blufsh liked this · 1 year ago

1fsh-2fsh-redfsh-blufsh liked this · 1 year ago -

beneath-the-willow-tree reblogged this · 1 year ago

beneath-the-willow-tree reblogged this · 1 year ago -

beneath-the-willow-tree liked this · 1 year ago

beneath-the-willow-tree liked this · 1 year ago -

ymfingsteadilyon liked this · 1 year ago

ymfingsteadilyon liked this · 1 year ago -

feralhobbit liked this · 1 year ago

feralhobbit liked this · 1 year ago -

lomeal liked this · 1 year ago

lomeal liked this · 1 year ago -

nobody-tosses-a-hutt liked this · 1 year ago

nobody-tosses-a-hutt liked this · 1 year ago -

ostenreal liked this · 1 year ago

ostenreal liked this · 1 year ago -

leannewinchester reblogged this · 2 years ago

leannewinchester reblogged this · 2 years ago -

leannewinchester liked this · 2 years ago

leannewinchester liked this · 2 years ago -

faery-snow liked this · 2 years ago

faery-snow liked this · 2 years ago -

lookitmychicken reblogged this · 2 years ago

lookitmychicken reblogged this · 2 years ago -

lookitmychicken liked this · 2 years ago

lookitmychicken liked this · 2 years ago -

galadhir reblogged this · 2 years ago

galadhir reblogged this · 2 years ago